John Shutske, Professor and Extension Agricultural Safety and Health Specialist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

What causes stress for farmers and farm families?

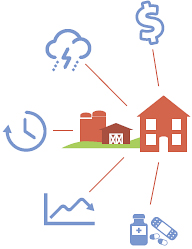

What causes stress for farmers and farm families?The list could continue endlessly for most people who work in agriculture. Farming is one of the most stressful occupations in the U.S. The following are some of the common stressors we encounter:

Stress is a double-edged sword. A little stress can serve as a constructive motivator, galvanizing us to action (Simon & Sieve, 2013). Too much stress, on the other hand, can damage our health (Donham & Thelin, 2016), compromise safety and sabotage personal relationships (Buck & Neff, 2012; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009). Stress diminishes our capacity for considering and evaluating alternative solutions to complex problems, thereby limiting our power to make sound decisions (Morgado, et al., 2015). Stress can also manifest itself as a vicious cycle with escalating consequences that can paralyze a farm family.

Stress is a double-edged sword. A little stress can serve as a constructive motivator, galvanizing us to action (Simon & Sieve, 2013). Too much stress, on the other hand, can damage our health (Donham & Thelin, 2016), compromise safety and sabotage personal relationships (Buck & Neff, 2012; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009). Stress diminishes our capacity for considering and evaluating alternative solutions to complex problems, thereby limiting our power to make sound decisions (Morgado, et al., 2015). Stress can also manifest itself as a vicious cycle with escalating consequences that can paralyze a farm family.

With the arduous and sometimes volatile conditions we see in agriculture, the risk of too much stress is alarming. Material here comes from more than two decades of working and spending time with farmers, agricultural service providers, community leaders, lenders, clergy, health professionals, educators and others in the industry to compile answers to these three questions:

Stress is our reaction to a threatening event or stimulus. Such events and stimuli are called “stressors.” People differ in how they perceive and react to stressors. Something one person would rate as highly stressful might be rated as considerably less stressful by someone else. Several factors influence our capacity for coping with stress:

When we encounter a stressor, our brain and body respond by triggering a series of chemical reactions that prepare us to engage with or run away from the stressor. Two hormones that we release are adrenaline, which prepares muscles for exertion, and cortisol, which regulates bodily functions. If a stressor is exceptionally frightening, it might cause us to freeze and become incapacitated (Fink, 2010).

The stress response causes our:

The stress response causes our:

Thousands of years ago, people who stumbled upon a hungry saber-toothed tiger or other predator would be more likely to survive the encounter if they were able to spring up and sprint away swiftly. An increase in blood pressure and heart rate and a slowdown of digestive processes meant more energy could be directed toward escaping. If they couldn’t run quickly enough, their odds of surviving a wound from the hungry tiger were better if their blood clotted rapidly.

Today, this physical response to stress can be damaging to our health. Unrelieved stress is a known risk factor in many of the leading causes of premature death among adults, including conditions and illnesses such as heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes and deterioration of the immune system (Mayo Clinic, 2016). Stress is also a risk factor for depression, addiction and suicide (Donham & Thelin, 2016).

Farming ranks as one of the most dangerous industries in the U.S. (National Safety Council, 2017). Stress, long hours and fatigue contribute to injury risk (Gerberich et al., 1998). When we confront several stressors at once, we may become distracted, and this distraction can cause errors that lead to serious or fatal incidents, such as tractor rollovers or entanglement in a fast-moving machine. Thus, proper safety precautions are essential for preventing such incidents.

Farm operators who face financial pressures while running a modern farming operation sometimes don’t invest in eliminating farm hazards. They might not replace damaged or missing shields on machinery. They may choose not to retrofit old tractors with rollbars and seatbelts. They might defer investments in equipment and facilities needed for safe animal handling and housing. Or they may require children to do potentially dangerous farm work before they are physically and mentally ready to perform these jobs safely. All farm safety efforts must include taking specific steps to better cope with the stress that operators and their families are likely to experience!

On page 6, you will find a “Top 10” list of farm safety tips based on the research and experience of safety specialists and researchers throughout the U.S.

During the last couple decades, researchers have learned how successful farmers and families effectively manage their stress by discussing their stress management methods with them. The actions described in this guide come directly from those discussions as well as suggestions from the larger agricultural community. Some of these actions involve preparing ourselves physically and emotionally to deal with stress. Other actions, such as planning and education, involve minimizing confusion and ambiguity and bolstering our levels of “hope” and perceived control.

During the last couple decades, researchers have learned how successful farmers and families effectively manage their stress by discussing their stress management methods with them. The actions described in this guide come directly from those discussions as well as suggestions from the larger agricultural community. Some of these actions involve preparing ourselves physically and emotionally to deal with stress. Other actions, such as planning and education, involve minimizing confusion and ambiguity and bolstering our levels of “hope” and perceived control.

It is important to recognize that it is impossible to totally eliminate all stress in any job, but effective management is possible.

Eat right: It sounds simple, but we don’t always do it! No farm operator would ever dream of feeding their animals lousy feed or heading out to the field in a combine with a half-filled tank of low-grade diesel fuel to complete harvest.

Yet when the rush season rolls around, we fill our bodies with cheap fast food and other low-nutrition junk. Or worse, we don’t eat at all! It’s worth the time to wake up a few minutes early to eat a quick breakfast and pack a nutritious lunch that includes fruits and vegetables to munch on during the day with limited amounts of fatty meats, added sugar and caffeine (Smith, 1998). An occasional cup of coffee or a can of soda is okay for most people if balanced with plenty of water – at least eight glasses a day.

Sufficient water intake is critically important during warm weather. Here’s an easy way to tell whether you’re hydrated: check the color of your urine. If it’s dark, you’re probably not drinking enough water (NIOSH, 2017).

Exercise is a natural and healthy stress reliever (Edenfield & Blumenthal, 2011). Physical activity provides an outlet for extra energy generated by the chemicals released in the body during stressful situations. Exercise stimulates and even increases the size of the parts of the brain that keep our stress response in check, as well as those needed for good decision-making and problem solving.

Exercise during the “off-season” prepares us for the long, strenuous work days during the spring and summer. If your doctor approves, a few minutes of walking or other aerobic exercise can have tremendous stress-relieving effects, and you will feel less exhausted at day’s end. An Olympic athlete or marathon runner wouldn’t tackle a grueling race without proper body preparation, and the demanding physical and mental work of farming is not all that different. Timely exercise eases the strain of vigorous physical activity and brightens our perspective.

Laughter can change our perception of an adverse situation and relieves us from the cycle of stress. It’s easier to laugh and regain perspective when we’re around other people, which is a reason why gathering places like coffee shops, restaurants, sporting events and churches are popular places during difficult times (Donham & Thelin, 2016).

One of the unfortunate consequences of too much stress is an increased risk of drug, alcohol or tobacco use and abuse. These substances may alter our perception in the short-term but often make challenging problems worse in the longer-term. Drug and alcohol abuse contribute to many farm and roadway injuries and incidents, and they can also damage our most precious relationships.

If you are concerned about drugs, alcohol, tobacco and your health and personal safety or the health and safety of a loved one, support and assistance are available (Donham & Thelin, 2016). Don’t be afraid or embarrassed to ask for help.

Have you ever been asked “What’s bugging you?” only to find yourself clamming up and not wanting to talk about it? This common reaction isn’t always harmful. However, openly discussing and airing problems, concerns, fears and frustrations can be constructive and healthy, which is especially true if we can move from the mode of being “cranky” to actively addressing the problem. Families and farm couples who handle stress well communicate freely. The process of admitting to worries and fears is sometimes difficult, but when all parties have open and clear access to information and can assist each other in finding solutions, problems become easier to solve (Donham & Thelin, 2016).

It’s vital to solicit assistance and advice from those in our community who are willing to help. Friends, extended family, church members and others in the community can often provide needed support. No matter who we talk to, vocalizing our concerns will alleviate the confusion and tensions that compound the feelings of stress.

As an industry, agriculture is becoming increasingly complex. Reports about biotech, big data, precision farming, complex marketing strategies and the latest changes in farm programs and tax policy are now commonplace in most major farm news outlets, which is why we should learn as much as we can. Successful operators have a handle on the latest and most effective production, marketing and finance-related practices and can take advantage of the latest technological developments. We’re never too old to learn, and there are many informal educational opportunities through local Extension offices, universities, technical colleges, university research stations and private sources such as crop consultants, veterinarians and sales reps.

Self-education requires time, energy and commitment, but it can lower stress by providing us with a mental roadmap that directs planning and decision-making. Successful producers who participate in educational opportunities feel less stressed as a result. Education builds confidence, and attending a class or an informal workshop series might open doors to new or supplementary business and financial opportunities.

Of all our resources, including land, animals, cash, fertilizer, seed and machinery, our minds are our most valuable asset.

Although we might dislike record-keeping, paperwork and planning, well-maintained records and evidence of a long-term plan are almost always required by lenders and others who allocate resources (Brotherson, 2017). Thorough planning requires an objective examination of current resources and future goals. This sometimes-onerous process of planning, goal-setting and record-keeping can be facilitated with the advice of accountants, attorneys, Extension educators, farm management specialists, state and local agencies and lenders.

Like education, the process of farm planning provides a roadmap that helps reduce confusion and ambiguity and thus reduces stress. These positive actions enhance the functioning and structure of our brains (Seo et al., 2014) and serve to create positive cycles of change and growth.

Have you ever missed a special family event like a parent-teacher conference or a family reunion because you were overwhelmed with work around the farm? Many of us have. While it might be unrealistic to shut down a complex operation for a couple hours to meet with our kid’s teacher, we often miss family events because we don’t go through the effort of planning. Missing these events can result in feelings of guilt, anger, regret and loss. By setting aside a few minutes each month to record important dates, events and meetings, we can prioritize our schedules to prevent ourselves from missing important moments. If conflicts arise, communication within the family will help everyone understand current deadlines and priorities, especially when schedules become hectic. This kind of communication establishes a team spirit and ensures key tasks around the home and farm will be managed rather than letting those tasks fall through the cracks.

Because of the high stress levels in farm communities, people who work in agriculture experience higher reported rates of depression and suicide. The checklist at right, provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (2016), lists some common symptoms of depression.

To help decide whether you or people you care about need support and treatment for depression, review this checklist and mark the symptoms that apply. If you experience any of these symptoms for longer than two weeks, if you feel suicidal or if the symptoms are severe enough to interfere with your daily life, see your family doctor and bring this list with you. As a first step, your doctor or another health professional may recommend a thorough examination to rule out other illnesses.

There are resources on suicide and suicide prevention that vary from state to state and across communities. If you’re thinking about suicide, worried about a friend or loved one or would like support, a Lifeline network is available 24/7 across the United States. It is free of charge and confidential. Call 1-800-273-8255 or visit SuicidePreventionLifeline.org.

Symptoms of clinical depression

- Persistent sad, anxious or “empty” mood

- Feelings of hopelessness, pessimism

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, helplessness

- Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities

- Decreased energy, fatigue, being “slowed down”

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, making decisions

- Difficulty sleeping, early-morning awakening or oversleeping

- Appetite and/or weight changes

- Thoughts of death or suicide, suicide attempts

- Restlessness, irritability

- Persistent physical symptoms

Change of any type is almost always a major stressor, and people who face the possibility of leaving or retiring from farming often report experiencing tremendous guilt and shame caused by a perception of legacy abandonment. These feelings are normal, and they are part of the grieving process any person goes through when they lose something or someone they love.

Remember that many of the structural and economic factors that drive changes in production agriculture are beyond our control. If you are struggling to keep pace with these changes, request support, expertise and assistance from qualified professionals. The choice of whether or not to leave farming is likely one of the most complicated and emotional ones that many farmers and their families will make in their lifetimes, but help is available – Do ask!

Top 10 farm safety tips

- Buy a rollover protective structure (ROPS) for older tractors. If an approved ROPS is not available, avoid using that tractor or consider trading or selling it through a local dealer.

- Replace all missing power take-off and rotating equipment shields. Shut off power equipment before leaving the operator’s station.

- Check that lights, flashers and reflectors on machines work properly. Always use them when traveling on roadways.

- Replace “slow moving vehicle” emblems that aren’t clean and bright.

- Inspect and repair farm machinery before the busy season. A well-maintained machine will operate more efficiently and reduce the chance of an injury.

- Use proper equipment and procedures when hitching and unhitching implements.

- Never enter a manure pit, grain bin or silo without following confined space entry procedures. The gases and materials in these structures kill farmers every year.

- Ensure that all workers receive specific instructions on their tasks and the machines they are operating. Be sure they read and understand all operational procedures in the owner’s manual.

- Take time to learn basic first aid, CPR and emergency response.

- Do not assign jobs to children unless they are physically, mentally and legally ready to perform the job safely, follow directions and can respond to unexpected situations. This may mean waiting until kids are at least 16 years of age.

Barlow, D. H. (2007). Forward. Principles and practice of stress management. (2nd ed.). P.M. Lehrer, R.L. Woolfolk, and W.E Sime (Eds.). New York, New York: Guilford Press.

Brotherson, S. (2017). Stress Management for Farmers/Ranchers. Retrieved from https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/publications/kids-family/farm-stress-fact-sheets-stress-management-for-farmers-ranchers

Buck A.A., Neff L.A. (2012). Stress Spillover in Early Marriage: The Role of Self-Regulatory Depletion. Journal of Family Psychology 26(5): 698-708. DOI: 10.1037/a0029260.

Donham, K. J., & Thelin, A. (2016). Agricultural Medicine: Rural Occupational and Environmental Health, Safety, and Prevention. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Edenfield, T. M., & Blumenthal, J. A. (2011). Exercise and stress reduction. The handbook of stress science: Biology, psychology, and health, 301-319.

Fink, G. (Ed.). (2010). Stress science: neuroendocrinology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Academic Press.

Gerberich, S. G., Gibson, R. W., French, L. R., Lee, T. Y., Carr, W. P., Kochevar, L., ... & Shutske, J. (1998). Machinery-related injuries: Regional Rural Injury Study—I (RRIS—I). Accident Analysis & Prevention, 30(6), 793-804.

Morgado, P., Sousa N. & Cerqueira, J. J. (2015). The impact of stress in decision making in the context of uncertainty. Journal of Neuroscience Research 93(6): 839-47. DOI: 10.1002/jnr.23521.

National Institute of Mental Health (2016). Depression. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression.

National Safety Council. (2016). Injury facts. Itasca, Illinois.

NIOSH - National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2017). Heat-related Illness. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/features/prevent-heat-illness.

Randall A.K., Bodenmann G. (2009). The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review 29(2): 105-15. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004.

Smith, A. P. (1998). Breakfast and mental health. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 49(5), 397-402.

Many of the recommendations in this publication come from the author’s 32 years of work in agricultural safety, health, wellness and stress management in both the public and private sectors. The information presented includes the wisdom of thousands of people who have participated in programs, participatory research and activities that engage the agricultural community. It also includes some of the latest science and published peer-reviewed research connected to how stress affects our brains, physical health, emotions and ability to process information and make decisions.

A comprehensive collection of citations, references and other materials is available from the author upon request.

John Shutske is a professor, Cooperative Extension Specialist and Director of the UW Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Shutske has over 30 years of experience working with the agricultural community, Extension educators, health professionals and agribusiness leaders. His work has focused on agricultural health, safety and risk control and communication. In addition to his faculty role in the Department of Biological Systems Engineering, Shutske also has an affiliate professor appointment in the UW-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health’s Department of Family Medicine and Community Health.

The University of Wisconsin Center for Agricultural Safety and Health is a joint effort of UW-Extension and the Department of Biological Systems Engineering, College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

For more information, contact: shutske@wisc.edu

Editorial support & assistance provided by Kelly Morehead, copyeditor

Reviewed by:

Roger T. Williams, Consultant/Mediator, University of Wisconsin-Madison Emeritus

Professor

Rachael Rol, Intern, National Farm Medicine Center and UW-Center for Agricultural Safety and Health

Daniel Lunetta, M.D. Candidate, Wisconsin Academy for Rural Medicine, and UW-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health

As an EEO/AA employer, University of Wisconsin-Extension provides equal opportunities in employment and programming, including Title VI, Title IX and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements.

If you need an interpreter, materials in multilingual or alternate formats or other accommodations to access this program, activity or service, please contact the language access coordinator at languageaccess@ces.uwex.edu as soon as possible to learn how to take the appropriate next steps. It is important to do this early in your planning process and prior to the scheduled event so that proper arrangements can be made in a timely fashion.

Graphic design by Jeffrey J. Strobel

UW Environmental Resources Center

Publication #: A-ASH-101 September 2017

Disclaimer and Reproduction Information: Information in NASD does not represent NIOSH policy. Information included in NASD appears by permission of the author and/or copyright holder. More