This guide is intended to help assist employers in the marijuana industry build occupational safety and health programs. While the foundation of this guide includes existing Colorado state and federal regulations, it is not a comprehensive guide to all of the regulations pertaining to occupational safety and health. It should be noted that this guide does not present any new occupational safety and health regulations for the marijuana industry.

For more information, please visit: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cdphe/marijuana-occupational-safety-and-health.

https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cdphe/marijuana-occupational-safety-and-health

Part 1: Background and Establishing a Safety and Health Program

Part 1: Background and Establishing a Safety and Health Program

Part 2: Guide to Worker Safety and Health in the Marijuana Industry

I.1 Biological hazards

I.1.1 Mold

I.1.2 Sensitizers/allergens

I.2 Chemical Hazards

I.2.1 Carbon dioxide (CO2)

I.2.2 Carbon Monoxide (CO)

I.2.3 Indoor air quality (IAQ)

I.2.4 Pesticides

I.2.5 Disinfectants/cleaning chemicals

I.2.6 Nutrients and corrosive chemicals

I.3 Physical hazards

I.3.1 Flammable/combustible liquids

I.3.2 Compressed gas

I.3.3 Occupational injuries

I.3.4 Ergonomics

I.3.5 Workplace violence

I.3.6 Walking and working surfaces

I.3.7 Working at heights

I.3.8 Electrical

I.3.9 Noise

I.3.10 Emergencies

I.3.11 Powered industrial trucks (forklifts)

I.3.12 Lighting hazards

I.3.13 Machines and hand tools

I.3.14 Extraction equipment

I.3.15 Confined spaces

Section II: Safety and Health Program Plans

At the time of this writing, 28 states and the District of Columbia currently have laws legalizing marijuana in some form. While many studies have focused on health outcomes and public safety issues, little attention has been focused on occupational safety and health associated with this industry. Prior to its legalization, occupational safety and health hazards associated with producing illegal marijuana were documented in published literature and law enforcement reports.1 Washington was the first state to develop formal guidance for the industry, such as the Regulatory Guidance for Licensed I-502 Cannabis Operations (https://fortress.wa.gov/ga/apps/sbcc/File.ashx?cid=4655). Our workgroup sought to identify various types of occupational hazards encountered in this industry and build a document to assist the industry and its workforce in building effective safety and health programs for their businesses. Our team included professionals with a variety of skill sets, including epidemiologists, medical doctors, industrial hygienists, safety professionals, and regulatory specialists, which resulted in a thorough review of the potential occupational safety and health issues in the industry. The State of Colorado Marijuana Enforcement Division’s (MED) Retail Marijuana Code, 1 CCR 212-1 and CCR 212-2, have specific regulations written for the marijuana industry in Colorado. This document is informational only and is not intended to replace or supplement regulations from Colorado’s MED Retail Marijuana Code or from the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). The best practices in this document are suggestions and do not establish any new enforceable regulations by the State of Colorado. Furthermore, this guide is not intended to provide a comprehensive list of existing federal, state, and local regulations that may apply to the marijuana industry.

The complicated nature of the hazards present in the marijuana industry highlights the need for careful attention to safety and health at all types of marijuana businesses. The purpose of this guide is to provide an overview of the safety and health hazards that may be present in the cultivation, processing and sale of marijuana. Not all hazards listed in this guide may be present at a given facility. Conversely, there may be additional hazards not listed within the scope of this guide that may be present at a given facility. This guide is intended to provide a starting point for the assessment and evaluation of occupational health hazards. This guide also provides abbreviated guidance and a list of resources to help employers in the marijuana industry develop an occupational health and program.

The objectives of this guide are to:

Guide roadmap

Part 1 of the guide begins with the initial steps that can be performed to establish a safety and health program within a facility. Given this initial background in Part 1, Part 2 provides more detail in two separate sections.

Section I

Section II

The final appendix that is included in this guide includes a table of OSHA regulations that may be applicable to the marijuana industry.

1 Martyny JW, S. K. (2013). Potential Exposures Associated with Indoor Marijuana Growing Operations. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene , 622-639.

ACGIH ® : American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. The ACGIH ® is a professional association of industrial hygienists and practitioners of related professions dedicated to promoting safety and health within the workplace. The organization is a professional society, not a government agency.

AIHA: American Industrial Hygiene Association. AIHA is one of the largest international associations serving occupational and environmental safety and health professionals practicing industrial hygiene and is a resource for those in large corporations, small businesses and who work independently as consultants.

Administrative controls: Policies, operating procedures, training programs, safe work practices, maintenance campaigns and other actions taken to prevent or mitigate workplace hazards.

Cannabis: Cannabis and marijuana are commonly used interchangeably. This document will use the term “marijuana” as this is the term used in Colorado legislation.

CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC is one of the major operating components of the Department of Health and Human Services. The CDC houses the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) whose mission is to develop new knowledge in the field of occupational safety and health and to transfer that knowledge into practice.

Cleaners: Products that remove dirt through wiping, scrubbing or mopping including soaps, detergents, and solvents.

CO: Carbon monoxide which is a colorless, odorless, and highly toxic gas most commonly produced indoors by incomplete combustion of natural gas or propane appliances or equipment.

CO2: Carbon dioxide which is a colorless, odorless gas that can displace oxygen at high concentrations and is used as a growth supplement in the marijuana industry.

Confined space: A space that is large enough for an employee to enter fully and perform assigned works; is not designed for continuous occupancy by the employee; and has limited or restricted means of entry or exit.

Disinfectants: Products that contain chemicals that destroy or inactivate microorganisms that cause infections. Commercial disinfectants must be registered with the Environmental Protection Agency.

EAP: Emergency Action Plan which is a workplace plan to make sure employees know what to do in case of emergency.

Ergonomics: The application of human biological sciences with engineering sciences to achieve optimum mutual adjustment of people and their work, the benefits measured in terms of human efficiency and well-being.

Engineering controls: Permanent features built into facilities or production processes to automatically eliminate or mitigate hazards. Primary engineering controls prevent hazards from ever occurring, and secondary engineering controls minimize damage after events occur.

EPA: Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA is responsible for the protection of public health and the environment by assuring compliance with federal environmental statutes and regulations.

FIFRA: Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act. The FIFRA provides for federal regulation of pesticide distribution, sale and use. All pesticides distributed or sold in the United States must be registered (licensed) by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Flammable liquid: Any liquid having a flashpoint at or below 199.4°F (93°C). Flammable liquids are divided into four categories:

Hypersensitivity diseases: Diseases characterized by allergic responses to chemicals or other substances, such as asthma, rhinitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

HVAC: Heating ventilation and air-conditioning system.

IAQ: Indoor air quality.

Industrial hemp: Amendment 64 to the Colorado Constitution defines industrial hemp as a plant of the genus cannabis and any part of that plant, whether growing or not, containing a Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration of no more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.

Job hazard analysis (JHA): A technique that focuses on job tasks as a way to identify hazards before they occur. It focuses on the relationship between the worker, the task, the tools and the work environment. After uncontrolled hazards are identified, this tool assists in outlining the steps to eliminate or reduce the hazards to an acceptable risk level.

NIOSH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH is a branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention whose mission is to develop new knowledge in the field of occupational safety and health and to transfer that knowledge into practice.

Occupational Health: Refers to the identification and control of the risks arising from physical, chemical, and other workplace hazards in order to establish and maintain a safe and healthy working environment.

OSHA: Occupational Safety and Health Administration. With the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, Congress created the OSHA to assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women by setting and enforcing standards and by providing training, outreach, education and assistance.

PEL: Permissible exposure limit. The PEL is the maximum amount or concentration of a chemical that a worker may be exposed to under OSHA regulations. This is usually expressed as an eight-hour, time-weighted average (TWA).

Permit-required confined space: A confined space that has one or more of the following: contains or has the potential to contain a hazardous atmosphere; contains a material with the potential to engulf someone who enters the space; has an internal configuration that might cause an entrant to be trapped or asphyxiated by inwardly converging walls or by a floor that slopes downward and tapers to a smaller cross-section; and/or contains any other recognized serious safety or health hazards.

PIT: Powered industrial truck. Any mobile power-propelled truck used to carry, push, pull lift, stack or tier materials. Powered industrial trucks can be ridden or controlled by a walking operator.

PPE: Personal protective equipment. PPE refers to protective clothing, helmets, goggles, or other garments or equipment designed to protect the wearer’s body from injury or infection.

REL: Recommended exposure limits. This is an occupational limit that has been recommended by the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health as being protective of worker safety and health over a working lifetime. It is frequently expressed as a time weighted average (TWA) exposure for up to 10 hours/ day during a 40-hour work week.

Sanitizer: A product that contains chemicals that reduce, but do not necessarily eliminate, microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses and mold from surfaces. Public health codes may require cleaning with the use of sanitizers in certain areas, like toilets and food preparation areas. As with disinfectants, some sanitizers will be registered with the EPA.

SDS: Safety data sheet, formerly known as Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS).

Sensitizer: A chemical or substance that causes a substantial proportion of exposed people or animals to develop an allergic reaction after repeated exposure to the chemical.

Terpene: Any large group of volatile unsaturated hydrocarbons found in the essential oils of plants. Terpenes are fragrant oils that can give marijuana its aromatic diversity.

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): The chemical that is the main mind-altering ingredient of cannabis.

TLV: Threshold limit value.

Veg Room: Where cloned marijuana plants from the nursery are grown to maturity before being moved into the flower room.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): Are emitted as gases from certain solids or liquids. VOCs include a variety of chemicals, some of which may have short- and long-term health effects. Concentrations of many VOCs are consistently higher indoors than outdoors. VOCs may be emitted while using solvents for extraction operations.

WHO: World Health Organization. The WHO is a global organization that is similar to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The organization publishes occupational health guidelines that can be supplemented in safety programs. Guidelines from WHO are not enforceable.

Employers are obligated to provide employees with current information about workers’ rights and labor laws as they relate to safety and health issues. All entities covered by OSHA are required to display the “OSHA Job Safety and Health: It’s the Law” poster in the workplace. This poster must be displayed in a conspicuous place where workers can see it. Copies of the poster can be accessed at : https://www.osha.gov/Publications/poster.html. In addition, Colorado employers may be required to post certain labor law posters. These posters can be accessed at: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cdle/posters.

As a part of a safety program, employers with one or more full-time or part-time employees are required by Colorado law to provide workers’ compensation insurance coverage for their employees, except for some specific exclusions. Coverage may be purchased from any authorized insurance company. If an employer fails, neglects or refuses to obtain workers’ compensation insurance as required by law, the Director of the Division of Workers’ Compensation is authorized to impose fines, and/or issue a cease and desist order against the business to stop operations until insurance is obtained. A contractor who contracts out any work to a subcontractor is liable for coverage for all workers of the subcontractor unless the subcontractor has obtained workers’ compensation insurance coverage.

Employers with more than 10 employees are required to keep a record of serious work-related injuries and illnesses. Minor injuries requiring first aid only do not need to be recorded. These records must be maintained at the worksite for at least five years. Each February through April, employers must post a summary of the injuries and illnesses recorded for the previous year. Per OSHA standard 29 CFR 1904.39, all employers are required to notify OSHA when an employee is killed on the job or suffers a work-related hospitalization, amputation, or loss of an eye. A fatality must be reported within 8 hours. An in-patient hospitalization, amputation, or eye loss must be reported to OSHA within 24 hours. For more detailed information on recordkeeping and reporting requirements: https://www.osha.gov/recordkeeping.

The framework for establishing a safety and health program has been adapted below from the OSHA framework described fully in https://www.osha.gov/shpmguidelines/SHPM_guidelines.pdf. The OSHA safety and health program framework is intended to provide employers, workers, and worker representatives with a sound, flexible method for addressing safety and health issues in diverse workplaces. It is intended for use in any workplace but will be particularly helpful in small and medium-sized workplaces. Many of the safety and health topics covered in other sections of this guide fit within the context of this safety and health program. A successful safety and health program should include the following elements within the framework: management leadership, worker participation, hazard identification and assessment, hazard prevention and control, education and training, and program evaluation and improvement. A sample program following the principles below can be found at https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/safetyhealth/mod2_sample_sh_program.html

Management provides the leadership, vision, and resources needed to implement an effective safety and health program. This includes a written policy signed by top management describing the organization’s commitment to safety and health and pledging to establish and maintain a safety and health program. Management can also establish goals to measure progress toward improved safety and health and allocate resources for pursuing these goals. An example management policy statement is located here: http://osha.oregon.gov/OSHAPubs/pubform/sample-policy-statement.doc

A safety and health program is dependent on worker participation in order to succeed. Workplaces should establish a process for workers to report injuries, illnesses, close calls/near misses, and other safety and health concerns, and respond to reports promptly. Reporting processes may have an anonymous component to reduce any fear of reprisal. Employees should also be given the opportunity to participate in every step of program design and implementation.The following document provides guidance in establishing management commitment and employee involvement in safety and health programs: https://www.osha.gov/dte/grant_materials/fy08/sh-17815-08/02_pg_module_2.pdf

A proactive, ongoing process to identify, assess, and mitigate hazards is a core element of any effective safety and health program. Failure to identify or recognize hazards is frequently one of the root causes of workplace injuries, illnesses, and incidents. This assessment process involves collecting information about workplace hazards and conducting inspections of the workplace in order to characterize hazards and determine effective controls.

Using tools such as a job hazard analysis (JHA) is one practical approach to identifying hazards and possible solutions to reduce or eliminate hazards. Examples and more information on developing a job hazard analysis can be found here https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3071.pdf.

Effective controls protect workers from workplace hazards; prevent injuries, illnesses, and incidents; minimize or eliminate safety and health risks; and help employers provide workers with safe and healthy working conditions. Controls are selected based on feasibility, effectiveness and permanence. Once controls are implemented, they should be evaluated to measure their efficacy and updated accordingly. This step might include a Hazard Communication Program, Hearing Conservation Program, Lockout/Tagout, or a PPE Assessment, all described in this guide in Section II.

Workers who know about workplace hazards, and the measures in place to control them, can work safer and more productively. Workers need to be trained on the safety and health program and their role as it relates to that program. They should also know how to identify workplace hazards and be involved in the process of controlling those hazards.

This step in the process helps establish a system of evaluating control measures for their continued effectiveness. Processes should be established to monitor program performance, verify program implementation, identify program deficiencies and opportunities for improvement, and take actions necessary to improve the program and overall safety and health performance.

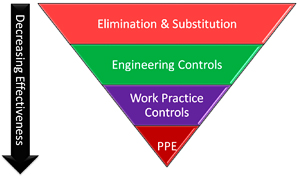

A number of control options exist when exposures or safety hazards are identified in the various occupational environments present in the marijuana industry. A well-known structure, the hierarchy of controls, has been successfully used to prevent worker injuries and illnesses in multiple industries.

Recognized as the most effective controls at reducing hazards, these include eliminating a hazard altogether from a specific process or substituting a less hazardous activity or chemical for a more hazardous one. These are most successfully implemented at the process design or development stage.

An engineering control is any change in facilities, equipment, tools, or process that eliminates or reduces a hazard. Engineering controls are designed to remove a hazard at its source before it comes in contact with the worker. Examples of engineering controls include process controls, isolation, and ventilation. Process controls involve changing the way a job or process is performed to make the work less dangerous (for example, using an electric motor instead of a diesel motor to eliminate exhaust emissions). Isolation controls keep employees isolated or physically removed from the hazard (for example, restricting employees from areas where intensive UV is being used).

Administrative controls are measures an employer can implement to reduce employee exposure to hazards by changing the way they work. Examples include employee breaks and worker rotation.

One might assume the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) to control identified hazards is a first step in protecting workers in the marijuana industry. However, within the hierarchy, PPE is actually the least effective method compared to elimination, substitution, or engineering controls and administrative controls. One reason PPE is the least effective control method is because it requires reliance on the worker to ensure it is used consistently and correctly. However, when hazards cannot be controlled through other means, PPE plays an important part in protecting workers.

In some settings, medical surveillance may be another strategy to optimize employee health. Medical screening is only one component of a comprehensive medical surveillance program. The fundamental purpose of screening is early diagnosis and treatment of the individual and has a clinical focus. The fundamental purpose of surveillance is to detect and eliminate the underlying causes such as hazards or exposures of any discovered trends and thus has a prevention focus. Using both medical screening and surveillance techniques can assist with the early identification of potential health hazards.

Upon multiple worksite observations and discussions with industry representatives, Table 5.1 summarizes job titles and associated types of potential hazards observed in the marijuana industry. Given the rapid evolution of this industry, the nature of businesses may continue to expand and consequently job titles, tasks, and hazards will also change. These roles should be considered throughout the program to ensure potential hazards are adequately recognized and reduced.

| Job | Duties | Potential hazards |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivator | Planting, transplanting, physically relocating plants, watering, nutrient mixing and feeding, mixing and applying pesticides, cleaning, harvesting plants, drying plants | Mold, sensitizers/allergens CO2, CO, pesticides/fungicides, ergonomics, walking/ working surfaces, lighting hazards, chemical exposures |

| Trimmer | Trimming, packaging, shipping, data entry, cleaning | Mold, sensitizers/allergens, CO2, CO, pesticides, ergonomics, occupational injuries (cuts), chemical exposures, machinery |

| Extraction technician | Extracting marijuana concentrates | Machinery, IAQ, allergens, noise, ergonomics, chemical exposures, use of explosive/ flammable chemicals such as butane |

| Edible producer, infused product confectioner/artisan/ chef | Cooking, baking, packaging, bottling, and labeling marijuana infused products | Occupational injuries (burns), noise, chemicals |

| Budtender | Sales representative who sells marijuana and marijuana products to customers | Sensitizers/allergens, ergonomics, workplace violence |

| Laboratory technician | Operates laboratory equipment to determine cannabinoid and contaminant concentrations | Solvents, ergonomics |

| Cultivation owner/operator | In addition to running the business, may oversee and be involved in the functions of the grow operation | Sensitizers/allergens, mold, CO2, CO, pesticides/fungicides, high pressure machinery, IAQ, noise, chemicals, workplace violence |

| Administrative | Responsible for day-to-day operations of the business. May include marketing roles, financial roles, HR roles, retail store management | Ergonomics, workplace violence |

| Transportation | May transport product or money between growing and retail facilities | Occupational injuries, workplace violence |

| Maintenance (non-contracted) | Facilities maintenance, equipment maintenance, HVAC | Elevated heights, electrical hazards |

Biological hazards can arise from directly working with plants. Biological agents can include bacteria and fungi that have the ability to adversely affect human health in a variety of ways, such as causing nasal congestion, throat irritation and other physical health effects. A summary of the potential biological hazards that may be encountered in the marijuana industry is presented in Table I.1.

| Hazard type | Hazard | Exposure level and/or applicable standards or guidelines | Health effects/ hazard | Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | Mold | WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Dampness and Mould | Nasal congestion, throat irritation, coughing, wheezing, eye irritation, skin irritation | Good housekeeping (moisture and dampness control), engineering controls (local and general exhaust ventilation), PPE |

| Sensitizers/allergens (dermal) | Varies | Irritant contact dermatitis, Allergic contact dermatitis | Medical surveillance, good housekeeping, proper PPE | |

| Sensitizers/allergens (respiratory) | Varies | Itchy, runny, or congested nose; sneezing; coughing; wheezing | Engineering controls, proper PPE |

Marijuana production requires increased levels of humidity, which have been found to be as high as 70 percent. This increased humidity in the presence of organic material promotes the growth of mold. Previous studies of illegal indoor growing operations have reported elevated levels of airborne mold spores, especially during activities such as plant removal by law enforcement personnel1. In this study, law enforcement personnel were exposed to levels of mold equivalent to a small to medium-sized mold remediation project. To date, there have not been similar studies of legal growing operations to determine the risk for mold exposure in the more controlled cultivation facility environments. Scientific reviews by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and WHO have indicated strong associations of exposure to indoor dampness related agents such as mold with health issues including wheezing, coughing, increased asthma symptoms, shortness of breath, and respiratory infections 1,2. A trained industrial hygienist can perform air monitoring to determine spore levels within the work environment. Special considerations may be needed for susceptible or immunosuppressed individuals. More research is needed to characterize and reduce potential exposures to mold and powdery mildew, including adverse effects on workers’ respiratory and lung functions.

Job roles affected: Employees within the cultivation facility and trimming room.

Hazard assessment: The facility should determine if the hazard is present and what controls or PPE might be needed for employee protection. Hazard assessments are contained within the Personal Protection Equipment Standard (See Section II).

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Case reports in the medical literature have described episodes of allergic reactions, hypersensitivity and anaphylaxis to marijuana3,4. Skin contact through personal handling of plant material or occupational exposure has been associated with hives, itchy skin, and swollen or puffy eyes. As with most sensitizers, initial exposure results in a normal response, but over time, repeated exposures can lead to progressively strong and abnormal responses. All of the hierarchy of controls can be used to help eliminate or reduce the effects of sensitizers or allergens.

Job roles affected: Employees who have direct contact with the marijuana plants.

Hazard assessment: Jobs roles that include coming in direct contact with plants should be evaluated and a PPE assessment completed. Hazard assessments are contained within the Personal Protection Equipment Standard (See Section II).

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

1IOM (Institute of Medicine) Damp Indoor Spaces and Health. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2004.

2WHO. (2009). WHO Guidelines for indoor air quality:dampness and mould. Retrieved 10 2016, from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/43325/E92645.pdf

3 Ocampo, TL and Rans, T. Cannabis sativa: the unconventional “weed” allergen.Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 114 (2015) 187-192.

4Decuyper II, Van Gasse AL, Cop N, Sabato V, Faber MA, Mertens C, Bridts CH, Hagendorens MM, De Clerck L, Rihs HP, Ebo DG. Cannabis sativa allergy: looking through the fog. Allergy 2016; DOI:10.1111/all.13043.

Chemical hazards pose a wide range of safety and health hazards. As discussed below, in order to ensure chemical safety in any workplace, information about the identities and hazards of the chemicals must be available and understandable to workers. A summary of some of the potential chemical hazards that may be encountered in the marijuana industry is presented in Table I.2.

| Hazard type | Hazard | Exposure level and/or applicable standards or guidelines | Health effects/ hazards | Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | Carbon dioxide (CO2) | OSHA PEL 5,000 ppm TWA | Asphyxiation, burns | Engineering controls, administrative controls (alarms/sensors), PPE |

| Carbon monoxide (CO) | OSHA PEL 50 ppm TWA | CO poisoning | Engineering controls, administrative controls (alarms/sensors) | |

| IAQ (Volatile organic compounds) | Varies depending on the VOC | Eye, nose and throat irritation, headaches, vomiting, dizziness, worsening asthma symptoms | Engineering controls (e.g., proper ventilation), administrative controls (e.g., proper handling and use), PPE | |

| Pesticides | EPA Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) EPA Worker Protection Standard 40 CFR Part 170 OSHA Hazard Communication 29 CFR 1910.1200 Colorado Pesticide Applicators’ Act Title 35 Article 10 and its Associated Rules |

Pesticide poisoning - effect varies depending on the nature of the pesticide; nervous system effects, skin or eye irritation, endocrine disruption, cancer | Engineering controls, administrative controls [e.g., standard operating procedures (SOPs)], PPE, Worker Protection Standards | |

| Disinfectants / cleaning chemicals | OSHA Hazard Communication 29 CFR 1910.1200. Disposal may be regulated under Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) |

Respiratory or skin irritation, burns, irritation of eyes, asthma, improper mixing of chemicals can cause severe lung damage | Engineering controls (ventilation), administrative controls (substitution), PPE | |

| Nutrients- Corrosives | OSHA Hazard Communization 29 CFR 1910.1200 Disposal may be regulated under Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) |

Respiratory, skin or eye irritation, burns to the skin and/or eyes, asthma, improper mixing of chemicals can cause severe lung damage | Administrative controls (substitution), Engineering controls (ventilation), PPE |

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is used in the marijuana industry to increase plant growth and to produce concentrates. In addition to the liquid gas form, solid carbon dioxide or dry ice can be used for extraction processes. Dry ice converts directly to carbon dioxide gas and can be hazardous to workers if not handled properly. In addition, CO2 might be used in compressed gas form for enrichment. Compressed gases can present a physical hazard that is described in this guideline under “Compressed gas” and has additional safety regulations that must be adhered to.

In normal concentrations, CO2 does not pose a health hazard. However, at high concentrations, CO2 acts as a simple asphyxiant. A simple asphyxiant is a gas or vapor that displaces oxygen. Most commercial CO2 systems are equipped with monitoring devices that will sound an alarm if an unsafe level of CO2 is detected in an area. These systems must be properly maintained and calibrated. Additionally, it is beneficial to train employees on the health effects associated with carbon dioxide so they are able to recognize symptoms in themselves or co-workers. Symptoms include headache, dizziness, rapid breathing, increased heart rate that can lead to unconsciousness, and death.

Job roles affected: Employees within the cultivation facility.

Hazard assessment: The facility should determine if the hazard is present and if controls or PPE are needed for employee protection. Hazard assessments contained within the Personal Protection Equipment Standard (See Section II). Carbon dioxide has an OSHA permissible exposure limit (PEL) of 5,000 ppm TWA.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless, toxic gas which interferes with the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood. At elevated concentrations, CO can overcome persons without warning. Many people die from CO poisoning, usually while using gasoline powered tools and generators in buildings or semi-enclosed spaces without adequate ventilation. Severe carbon monoxide poisoning can cause neurological damage, illness, coma and death. Sources of carbon monoxide exposure include furnaces, hot water heaters, portable generators/ generators in buildings; concrete cutting saws, compressors; fork lifts, power trowels, floor buffers, space heaters, welding, and gasoline powered pumps.

Jobs affected: Employees within the cultivation facility, employees in areas where generators may be running or indoor equipment is being used.

Hazard assessment: The facility should determine if the hazard is present and if ventilation or PPE is needed for employees. Potential sources of CO should be evaluated. Hazard assessments are contained within the Personal Protection Equipment Standard (See Section II).

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Workers may encounter ozone as a product of the chemical reaction of nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds (e.g., terpenes emitted from the marijuana plant) present inside a cultivation facility. Nitrogen oxides may enter the facility, depending on the location of air intake and proximity to major highways. Terpenes and nitric oxides are associated with eye, skin and mucous irritation. Ozone generators may also be found in facilities for odor control. Ozone can cause decreased lung function and/or exacerbate pre-existing health effects, especially in workers with asthma or other respiratory complications. More research is needed to characterize potential exposures to ozone, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds in marijuana cultivation operations.

Job roles affected: Employees working in indoor environments may be subject to IAQ issues at any time.

Hazard assessment: Ensure HVAC systems are adequate for the facility where they are located. Many IAQ problems result from poor ventilation (lack of outside air), problems controlling temperature, high or low humidity, recent remodeling, and other activities in or near a building that can affect the fresh air coming into the building. Sometimes, specific contaminants like dust from construction or renovation, mold, cleaning supplies, pesticides, or other chemicals may cause poor IAQ.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards

Resources for program development:

Marijuana cultivation facilities may have insecticides and fungicides used within the facility. Some pesticides, including pyrethrins and neem oil are non-persistent and have low volatility. However, these pesticides have been associated with dermal and respiratory toxicity for the workers who apply them. Workers applying pesticides without proper personal protective equipment may be placing themselves at risk. Applicators need to know the product, use the product according to the label and understand the product’s toxicity. Unlabeled or unknown products should never be used and would be a violation of Colorado State Law, under the Pesticide Applicators’ Act to do so. Depending on the pesticide used, requirements from 40 CFR Part 170 also known as the EPA’s Agricultural Worker Protection Standard or WPS may need to be implemented. When a pesticide product has labeling that refers to the WPS, WPS codes will be enforced.

The WPS requires that owners and employers on agricultural establishments:

The WPS is an extensive rule all agricultural establishments must comply. The Colorado Department of Agriculture can provide information specific to the WPS by contacting Mike Rigirozzi at 303-869-9059 or michael.rigirozzi@state.co.us.

The Colorado Department of Agriculture has adopted rules setting criteria for allowable pesticides for use in the cultivation of cannabis in Colorado. These rules became effective March 30, 2016. A list of pesticides allowed for use in cannabis production in accordance with the Colorado Pesticide Applicator Act can be accessed at https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Pesticides%20allowed%20for%20use%20in%20cannabis%20production%208-4-16.pdf.

In addition to reading and following labels for correct pesticide use, labels should also be followed for the proper disposal of pesticide containers.

Job roles affected: Employees within the cultivation facilities. If WPS is referenced on the pesticide label, the WPS standard covers pesticide handlers: those who mix, load, or apply agricultural pesticides; clean or repair pesticide application equipment; or assist with the application of pesticides. The WPS standard also covers agricultural workers: those who perform tasks related to growing and harvesting plants in greenhouses or nurseries.

Hazard assessment: Hazard assessment for pesticide use should involve the following:

Best practices:

State/federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Employers must provide safe working conditions for employees using cleaning chemicals. Even if store bought household disinfectants and cleaners are used employees should be warned of their potential hazards. EPA- registered antimicrobials fall under pesticide registration and must be used in a manner consistent with the product labeling. These chemicals should be a part of the facility hazard communication plan (Section II). When chemicals such as bleach are used routinely, they can be corrosive to surfaces and could affect employees using the products by causing respiratory and skin irritation. In addition, injuries with spills and splashes can occur when cleaning. There are a variety of cleaning and disinfectant chemicals on the market. The least hazardous cleaning chemical that best suits the purpose for which it will be used should be chosen. If sanitizing or disinfecting is necessary, the product purchased should be effective against the microorganisms being targeted. These products are primarily intended for use as hard surface disinfectants, they are not intended to be applied directly to crops to control pest problems. Use in a manner inconsistent with the labeling would be a violation of the Colorado Pesticide Applicators’ Act.

Job roles affected: Employees who are responsible for housekeeping and anyone using disinfectants or cleaning chemicals.

Hazard assessment: Hazard assessment for disinfectants and cleaners should involve selection of the least hazardous chemical, ensuring safe working conditions exist, such as adequate ventilation, for employees using cleaning chemicals, and PPE compatibility and accessibility is assessed. Hazard assessments are contained within the Personal Protection Equipment Standard (See Section II).

Best practices:

State/federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Cultivation facilities may encounter corrosive chemicals in the mixing of nutrients used for plant growth. Corrosives are materials that can attack and chemically destroy exposed body tissues. Corrosives can also damage or even destroy metal. The stronger or more concentrated, the corrosive material is and the longer it touches the body, the worse injuries can be. Corrosive materials can severely irritate, or in some cases, burn the eyes. Skin can become badly burned or even blister on contact with corrosive chemicals. Respiratory hazards can also occur from breathing in corrosive vapors or particles that irritate or burn the inner lining of the nose, throat and lungs.

Most corrosives are either acids or bases. Common acids include hydrochloric acid, phosphoric acid, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, chromic acid, acetic acid and hydrofluoric acid. Common bases are ammonium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, and sodium hydroxide. Chemicals used in both liquid and solid forms should be a part of a hazard communication plan (Section II) and should be stored away from incompatible materials.

Job roles affected: Employees in cultivation areas. Employees who mix plant nutrients.

Hazard Assessment: Hazard assessment for nutrients and chemicals used should involve selection of the least hazardous chemical. Ensure safe working conditions, such as adequate ventilation, for employees using corrosive chemicals, and assess PPE compatibility and accessibility. Hazard assessments are contained within the Personal Protection Equipment Standard (See Section II).

Best practices:

State/federal Standards:

Resources for program development:

Physical hazards include hazards that might exist within the workplace that can cause physical harm or injury. Many of the hazards listed below have different regulations and work practices that should be followed to ensure a safe work environment. A summary of the potential physical hazards that may be encountered in the marijuana industry is presented in Table I.3.

| Hazard type | Hazard | Exposure level and/or applicable standards or guidelines | Health effects/hazard | Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Compressed gases | Compressed gases - 29 CFR 1910.101 | Explosion hazards, fire | Administrative controls (proper use and handling) |

| Occupational Injuries (sharp objects, hot/cold surfaces) | OSHA General Duty Clause 5(a)(1) | Cuts, burns, infection | Engineering controls, administrative controls, PPE | |

| Ergonomics, body mechanics | OSHA General Duty Clause 5(a)(1) | Muscle, nerve, and tendon injury | Engineering controls, administrative Controls | |

| Workplace violence | OSHA General Duty Clause 5(a)(1) | Injury, mental health effects | Engineering controls, administrative Controls | |

| Walking working surfaces | OSHA Standard 1910 Subpart D | Slips, trips and/or falls | Engineering controls, administrative controls | |

| Working at heights | OSHA Standard 1910.24- 1910.29 1910 Subpart F | Fall from heights | Engineering controls, administrative controls, PPE (fall protection) | |

| Electrical | OSHA Standard 1910 Subpart S | Burns, shock, electrocution | Engineering controls, administrative controls, PPE | |

| Noise | 85 dBA (action level for 8 hr TWA/OSHA Standard 1910/95/90 dBA TWA | Temporary or permanent hearing loss | Engineering controls, administrative controls, PPE | |

| Environment | OSHA Standard 29 CFR 1910 Subpart E; 29 CFR 1910.39; 29 CFR 1910.38 | Fire, natural disasters, extreme weather | Engineering controls, administrative controls | |

| Powered industrial trucks (PITs)(forklifts) | OSHA standard 1910.178 | Driving accidents, accidents involving heavy/ awkward loads | Engineering controls, administrative controls | |

| Lighting hazards | OSHA Standard 1910.1096 | Eye and skin damage | Engineering controls, administrative controls, PPE |

|

| Machines | OSHA Standard 1910.212 | Burns, explosions, hand injury, entrapment | Engineering controls, administrative controls, PPE | |

| Extraction equipment | Denver Fire Department Marijuana Extractions guideline | Burns, explosions, fire, injury | Engineering controls, administrative controls, PPE | |

| Confined spaces | OSHA Standard 1910.146 | Entrapment, asphyxiation, engulfment, injury | Engineering controls, administrative controls |

Flammable and combustible liquids are liquids that can burn. Flammable and combustible liquids are present in almost every workplace, including the marijuana industry. Fuels and products such as solvents, thinners, cleaners, adhesives, paints, waxes and polishes may be flammable or combustible liquids. They are classified, or grouped, as either flammable or combustible based on their flashpoints. In general, flammable liquids will ignite and burn easily at normal working temperatures (below 37.8°C (100℉)). Combustible liquids have the ability to burn at temperatures that are usually above working temperatures (above 37.8 °C (100 ℉) and below 93.3°C (200℉). Containers of Category 1 or 2 flammable liquids or Category 3 flammable liquids with a flashpoint below 100°F (37.8°C) are required to be bonded and grounded. Bonding and grounding should always be used when dispensing flammable liquids as well.

Job roles affected: Processors and anyone who might handle or be around flammable or combustible liquids within a facility.

Hazard assessment: Hazard assessment for work involving flammable liquids should thoroughly address the issues of proper use and handling, fire safety, chemical toxicity, storage and spill response. This can be completed by conducting a chemical inventory and reviewing the SDS for each chemical that can help to determine the proper handling, use of the chemical and procedures to follow in the event of a spill or chemical release.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Compressed gas in the marijuana industry can consist of gases used such as CO2 for enrichment purposes or gasses used for extraction processes. Large quantities of compressed gas in facilities with improper training and inadequate procedures can pose a serious threat to employee safety. All compressed gases are hazardous because of the high pressures inside the cylinders. Most cylinders have safety-relief devices. These devices can prevent rupture of the cylinder if internal pressure builds up to levels exceeding design limits. However, gas can be released deliberately by opening the cylinder valve, or accidentally from a broken or leaking valve or from a safety device. There have been many cases in which cylinders have become uncontrolled rockets or pinwheels and have caused severe injury and damage. In addition, pressure can become dangerously high if a cylinder is exposed to fire or heat, including high storage temperatures.

As stated in the extraction equipment Section I.3.14, the Denver Fire Department has issued a Marijuana Extraction Guideline for Commercial/ Licensed Facilities that provides further guidance on the applicable codes for extraction equipment and associated chemical materials including compressed gases. This Denver code requires that extraction equipment approval is required from the Denver Fire Department for use in the City and County of Denver. Marijuana cultivators outside of the City and County of Denver should consult their local jurisdiction regulations.

Job roles affected: Extraction technicians and anyone using or handling compressed gases.

Hazard assessment: A hazard assessment for work involving compressed gasses should thoroughly address the issues of proper use and handling, fire safety, chemical toxicity, storage and spill response

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development

Employees in any industry are susceptible to potential injury (work-related or not), which could be anything from slips, trips, or falls, to an auto accident or heart attack. Many minor injuries or health-related incidents that occur in the workplace can be treated immediately using first aid. In more severe cases, first aid, CPR, or the use of an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) can help reduce the long-term severity of an injury or incident by providing temporary treatment until professional help can be obtained. Some locations may be too far from immediate emergency services and need to have employees with first aid training.

To handle potential workplace injuries, employers must ensure medical personnel and adequate first aid supplies are available to workers. Procedures should be developed to ensure medical personnel are ready and available for advice and consultation on the overall employee safety and health condition in the workplace. In addition, suitable facilities for immediate emergency use should be provided if exposure to injurious or corrosive materials is possible. Facilities should also use a “universal precautions” approach to infection control to treat all human blood and certain body fluids as if they were known to be infectious for HIV, HBV and other bloodborne pathogens. This involves avoiding contact with bodily fluids by wearing non-porous articles such as gloves, goggles and face shields.

Job roles affected: Common exposures for cuts include job roles that involve the use of trimmers and scissors, opening packages, and using knives for cutting tape and labels as well as other tasks. Burns can occur in operations involving food production, kitchens or when using cleaning chemicals. There is also the possibility of burns while changing tubing on compressed gases or from improper use of canned air.

Hazard assessment: Employers should make an effort to obtain estimates of emergency medical system (EMS) response times for all permanent and temporary locations and for all times of the day and night at which they have workers on duty, and they should use that information when planning their first-aid program. When developing a workplace first-aid program, it may help to consult the local fire and rescue service or emergency medical professionals for response-time information and other program issues.

Best practices:

State/federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Ergonomics is the study of how humans interact with manmade objects. The goal of ergonomics is to create an environment that is well-suited to a user's physical needs. It is an applied science concerned with designing and arranging things people use so the people and things interact most efficiently and safely. Employers are responsible for providing a safe and healthful workplace for their workers. In the workplace, the number and severity of musculoskeletal disorders resulting from physical overexertion and their associated costs can be substantially reduced by applying ergonomic principles.

Job roles affected: Job roles such as trimming marijuana leaves or manual cultivation activities have tasks that might present awkward postures, high hand forces, highly repetitive motions, repeated impacts, heavy, frequent or awkward lifting; or moderate-to-high hand-arm vibration may be at risk for cumulative trauma disorders (CTDs), repetitive stress injuries (RSIs) or musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs).

Hazard assessment: Employers are encouraged to conduct a worksite analysis to identify ergonomic hazards and conditions by tracking injury and illness records to identify patterns of trauma or strains associated with particular job tasks that may indicate the development of MSDs or CTDs. Once these job tasks are identified, a risk assessment can be performed to evaluate the risk for an MSD. Major risk factors that may lead to cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremities (hands and arms) include:

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

There may be a false sense of security or general lack of awareness regarding workplace violence in the marijuana industry. The most obvious opportunity for violence is in growing operations and retail stores, due to the presence of large quantities of cash and product, the possibility of disgruntled employees, angry terminated employees, and a high-stress environment. Other routine activities such as moving large quantities of product between stores, transporting product in personal vehicles and making trackable movements (times and routes) create opportunities for a violent offender to attempt robbery. Workplace violence can take many forms including verbal threats, threatening behaviors or physical assaults. Violence can be committed by strangers, customers or clients, co-workers, or by personal relations.

Security in the marijuana industry is highly regulated by the Colorado Marijuana Enforcement Division (MED) due to the potential for crime against businesses with large amounts of product and/or money on the premises. Specific regulations can be accessed at: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/enforcement/laws-constitution-statutes-and-regulations-marijuana-enforcement. These regulations include the placement of alarms and video surveillance as well as specific requirements to maintain visitor logs in limited access areas and signage to indicate ingress and egress to limited access areas. However, that security should not interfere with employees’ ability to exit the building in the event of an emergency, or with responders’ ability to enter.

Job roles affected: According to OSHA, research has identified factors that may increase the risk of violence for some workers at certain worksites. Such job roles in the marijuana industry at increased risk of violence include retail roles, employees working alone or in isolated areas, employees transporting marijuana products and cash to retail facilities, and employees working late at night or in areas with high crime rates. However, security should be assessed for all roles within the industry.

Hazard assessment: Employers are encouraged to conduct an assessment of the workplace to find existing or potential hazard for workplace violence. By assessing worksites, employers can identify methods for reducing the likelihood of incidents occurring. This assessment can include analyzing and tracking records of violence at work, examining specific violence incidents carefully, surveying employees to gather their ideas and input, and periodic inspections of the worksite to identify risk factors that could contribute to injuries related to violence.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Regardless of the industry someone works in, workers and visitors to facilities can all be prone to slip, trip, and fall hazards both indoors and outdoors. Some of the causes of slip, trip, and fall injuries include:

Job roles affected: All employees are prone to slip, trip and fall hazards. A facility hazard assessment should be conducted to identify potential slip, trip, and fall hazards in the workplace and these should be eliminated or modified to reduce the fall potential.

Hazard assessment: Both slips and trips result from some kind of unintended or unexpected change in the contact between the feet and the ground or walking surface. Good housekeeping, quality of walking surfaces (flooring), selection of proper footwear, and appropriate pace of walking are critical for preventing fall accidents.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Falls from portable ladders (step, straight, combination and extension) are one of the leading causes of occupational fatalities and injuries. There are a number of ways employers can protect workers from falls, including using conventional means such as guardrail systems, safety net systems and personal fall protection systems, adopting safe work practices and providing appropriate training. Whether conducting a hazard assessment or developing a comprehensive fall protection plan, thinking about fall hazards before the work begins will help the employer manage fall hazards and focus attention on prevention efforts. If personal fall protection systems are used,particular attention should be paid to identifying attachment points and ensuring employees know how to properly use and inspect the equipment.

Job roles affected: Employees who use ladders and scaffolds, including step stools/ step ladders.

Hazard assessment: Determine which specific jobs, activities or areas expose employees to fall hazards. Determine if employees will be exposed to any of the following: unprotected sides and edges, leading edges, floor holes, portable ladders and stairways, working above dangerous equipment, working overhead, roof work, aerial lifts, and scaffolds.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

The cultivation of marijuana is a very energy intensive process. Common electrical hazards include the use of temporary wiring (e.g., extension cords), missing breakers, blocked electrical panels, improperly wired units, electricity use in high humidity and watering areas, improper repairs, unguarded fans, overloaded circuits, inadequate wiring, lack of training and general electrical safety. National electric codes as well as local building and fire codes should be applied to assist to eliminate the need for temporary wiring in a cultivation facility. Ensuring that electrical equipment and their power cords are in good working condition will reduce the potential of electrical shock and injury.

The OSHA lockout/tagout standard establishes the employer’s responsibility to protect employees from hazardous energy sources on machines and equipment during service and maintenance. Information on developing a lockout/ tagout program is located in Section II of this document.

Job roles affected: Employees who may be working with our around electrical sources.

Hazard assessment: A hazard assessment of the workplace should be completed to develop a current listing of potential hazard areas, activities, or processes associated with electrical systems. This analysis will provide a basis for defining work-specific hazards associated with electricity and create a plan for hazard mitigation and employee training.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

OSHA estimates nearly 30 million workers every year are exposed to hazardous levels of noise. Exposure to hazardous levels of occupational noise can cause noise-induced hearing loss. Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is a reduction in a person’s ability to hear sound due to exposure to hazardous levels of noise. This damage can be irreversible. Noise levels can be variable within the different areas of cultivation facilities. Specific tools or machines that are being used can contribute to high noise levels in the facility.

To protect workers from NIHL OSHA has set an action level of 85 decibels (dbA). OSHA requires employers to institute a hearing conservation program when workers are exposed to noise levels at or above the action level of 85 dBA. An industrial hygienist or safety specialist can perform noise monitoring to determine noise levels within the work environment. Generally, if a job process or operation is occurring in an area where voices need to be raised from a normal conversations sound level, these areas may be above the action level of 85 dBA and warrant further investigation.

Job roles affected: Employees working with or around loud machinery such as around power tools, compressors, or wood chippers.

Hazard assessment: Monitor and document sound levels in areas where noises cause a worker to raise his or her voice above normal conversation levels to be heard. Personal monitoring with dosimeters can also assess noise levels encountered by employees.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Emergencies such as fires and natural disasters can be a hazard in any industry. The most important aspect of preparation is ensuring prevention programs are put in place. Facilities need to have an Emergency Action Plan (EAP) as required by OSHA. Emergency Action Plans (EAPs) should clearly establish employee roles and responsibilities, evacuation routes, and meeting locations during an emergency. Routine fire department inspections will help ensure compliance with fire extinguishing and sprinkling facility code requirements. It is essential to know where fire suppression systems are located and how to use fire extinguishers. Natural disasters such as tornados and potential workplace violence situations such as active shooter situations should also can be covered in an emergency action plan.

Job roles affected: All workers should participate and be aware of emergency action plans.

Hazard assessment: In most circumstances for fires, immediate evacuation is the best policy, especially if professional firefighting services are available to respond quickly. There may be situations in which employee firefighting is warranted to give other workers time to escape or to prevent danger to others by the spread of a fire. Shelter-in-place might be warranted in the case of a tornado. Consider including active shooter scenarios in the EAP. See Section II for additional fire protection policy and Emergency Action Plan guidance.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

There are many types of powered industrial trucks (PITs). Each type presents different operating hazards. Workers can be injured:

Forklifts are primarily used to transport and move materials and come in many sizes and capacities. They can be powered by batteries, propane, gasoline or diesel fuel. Whenever forklifts are in use, operation programs must be established that outline the operation of the forklift as well as the training of the operator. In addition, the workplace where the forklift will be operated must be considered. In warehouse areas, such as might be found in marijuana cultivation facilities, pedestrian traffic must be considered when forklifts are in use. Forklift traffic and pedestrian traffic should be separated when possible. Forklift operation programs should also include inspection programs and additional safety measures that should be employed when powered industrial trucks are used in the workplace.

Job roles affected: Employees who are responsible for the operation of PITs (forklifts). Employees who might be working in areas where PITs (forklifts) are operated.

Hazard assessment: Determining the best way to protect workers from injury largely depends on the type of truck and the worksite where it is being used. Employers must ensure each powered industrial truck operator is competent to operate a powered industrial truck safely, as demonstrated by the successful completion of the training and evaluation specified in 29 CFR 1910.178(l)(1).

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Metal halide lights, which are often used in veg rooms, contain an inner arc tube that is similar to a welder’s arc. This arc emits intense UV radiation along with visible light. Normally the outer glass bulb reduces the ultraviolet (UV) radiation to nominal levels, but, if the outer bulb is broken, UV levels can be significant enough to cause photokeratitis. Photokeratitis is a painful eye condition that occurs when your eye is exposed to invisible rays of energy called ultraviolet (UV) rays, either from the sun or from a man-made source. Symptoms, which include tearing, blurry vision, and the feeling of a foreign body in the eye, normally peak six to 12 hours after exposure. To prevent photokeratitis, broken metal halide bulbs should be immediately removed from service.

UV lamps can be useful germicidal tools. As with metal halide lights, exposure to UV radiation from these lamps can cause extreme discomfort and serious injury. The effect of UV radiation overexposure depends on UV intensity, wavelength, portion of the body exposed, and the sensitivity of the individual. Overexposure of the eyes may produce painful inflammation, a gritty sensation, and/or tears within three to 12 hours. Overexposure of the skin may produce reddening (sunburn) within one to eight hours. Certain medications can cause an individual to be more sensitive to UV light.

Fluorescent lamps may also be used in marijuana cultivation facilities. Health hazards with fluorescent bulbs are present when a fluorescent bulb breaks. The hazard is from metals such as lead, cadmium and, most importantly, mercury. Broken bulbs can release mercury vapors causing exposure to employees in the area of the broken lamp.

In addition to considering the health effects of lighting, there also must be a hazardous waste plan for disposing of spent or broken bulbs. Mercury containing lighting wastes such as fluorescent, high-pressure sodium, mercury vapor and mercury halide lamps are classified as “Universal Waste” and is covered under the Colorado Hazardous Waste Regulations and under the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).

Job roles affected: Employees who are working in areas where metal halide and/or other high-intensity lights are being used.

Hazard assessment: Operators of UV-generating equipment for which the radiation is not totally enclosed and exposure is possible should wear PPE to protect them from the long-term effects of UV radiation. These areas should be isolated from the general public entrance.

Best practices:

State/ federal standards:

Resources for program development:

In addition to high-pressure machinery for extractions, grinders, trimming machines or wood chippers might be used at marijuana cultivation facilities. For all machinery, it is key that preventative maintenance programs are put into place to ensure safe operation. In addition, a lockout/tagout program may be needed to ensure hazardous energy is isolated prior to machine maintenance (Section II). Employees who use hand and power tools and are exposed to the hazards of falling, flying, abrasive and splashing objects, or to harmful dusts, fumes, mists, vapors, or gases must be provided with the appropriate PPE.

Job roles affected: Employees who operate machines.

Hazard assessment: Assess machines for motion hazards such as pinch points or exposed rotating parts and actions such as cutting, punching, shearing or bending. Assess machine safeguards to ensure they meet the minimum OSHA requirements. Safeguards should prevent workers’ hands, arms and other body parts from making contact with dangerous moving parts or areas of high heat. A machine-guarding checklist can be used to assist with assessment.

Best practices:

State/federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Performing extractions is probably one of the most well known physical hazard in the marijuana industry. With the processes that are commonly used there is a large explosion and fire hazard when extracting oils from the marijuana plant. In response to this known hazard, the Denver Fire Department has developed extraction guidelines for commercial/ licensed facilities that clarify the code requirements of the 2016 Denver Fire Code (2015 International FIre Code with Denver Amendments) Chapter 39. Local municipalities fire codes should also be consulted if the marijuana facility is outside the Denver Metro Area. However, the Denver Fire Codes to provide a framework for extraction safety and provide detailed construction and equipment standards that can assist in developing a safe extraction practice.

High heat and pressure may be combined to make products like rosin. High-pressure machinery poses a hazard both from the pressing and high pressure build-up to extract oils and from explosion hazards and burns. CO2 is commonly used for extractions and is covered under its own section in this document. Extraction using butane is the most cost effective yet the most dangerous method of extraction used. Open releases of butane to the atmosphere during extractions is prohibited by Denver Fire Code. Extraction equipment that use hazardous materials (i.e. flammable/ combustible liquids, Carbon Dioxide (CO2), liquefied petroleum gases (i.e. butane)) are required to be listed or approved per the Denver Fire Code. Only closed-loop type liquefied petroleum gas extraction equipment is permitted. This equipment must further be approved by the Denver Fire Department before use.

Distillation or evaporative extraction/ refinement processes may also be used in the extraction process. As with other electrified equipment, equipment used in these processes should be listed by a Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratory (NRTL) for their intended use and are required to be operated within the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Job roles affected: Employees involved in extraction processes.

Hazard assessment: If extraction processes are going to be utilized, local fire codes must be consulted. The 2016 Denver Fire Codes detail equipment and facility construction that needs to be put into place prior to performing extractions. Hazard assessments similar to what has been done for chemicals, gasses, flammable/ combustible liquids should be followed. PPE assessments for employees should be performed. (Section II).

Best Practices:

State/federal standards:

Resources for program development:

Confined spaces are work areas that are large enough for an employee to enter, have limited means of entry or exit, and are not designed for continuous occupancy. These spaces can present physical and atmospheric hazards that can be prevented if addressed prior to entering the space to perform work. By this definition, water storage tanks used in many grow operations are confined spaces. People working in confined spaces can face life-threatening hazards including toxic substances, electrocutions, explosions, and asphyxiation. In the marijuana industry, examples of confined spaces are water tanks, cold storage areas, and manholes.

OSHA uses the term "permit-required confined space" (permit space) to describe a confined space that has one or more of the following characteristics:

One example of a permit-required confined space is a water storage tank that is entered in order to perform cleaning tasks using chemical cleaners.

Job roles affected: All employees must be aware of confined and permit required spaces. Special training is required for employees who are entering permit-required confined spaces.

Hazard assessment: Employers should inspect the workplace to determine if any confined spaces exist. If confined spaces exist within the facility, employees must be notified of the existence and location of and the danger posed by the permit spaces.

Best practices:

State/federal standards:

Resources for program development:

The Hazard Communication Standard requires employers to inform employees of hazards and identities of chemicals they are exposed to in the workplace, as well as protective measures that are available. All workplaces where employees are exposed to hazardous chemicals must have a written plan that describes how the hazard communication standard will be implemented in that facility.

The steps for implementing an effective hazard communication program are:

1. Learn the standard and identify responsible staff

Obtain a copy of the standard from OSHA, and designate an individual responsible for implementing this standard.

2. Prepare and implement a written hazard communication program

Address how you will meet the requirements of the standard, and include a list of all hazardous chemicals in the workplace.

3. Ensure containers are labeled

Manufacturers of hazardous chemicals are required to label, tag or mark the chemical with the identity of the material and appropriate hazard warnings. If materials are transferred into other containers, employers may create their own workplace labels. They either can include all the required information on the label from the chemical manufacturer, or the product identifier and words, pictures and symbols, or a combination thereof, which in combination with other information immediately available to employees, provides specific information regarding the hazards of the chemicals.

4. Maintain safety data sheets (SDS)

Safety data sheets include information about hazardous chemicals, including identification, hazards, first-aid measures, and handling and storage precautions. Manufacturers are required to provide SDS. These sheets must be maintained by employers for all hazardous chemicals in the workplace and be readily available to employees.

5. Inform and train employees

Employees must be trained on hazardous chemicals in their work areas before their initial assignment, and whenever new hazards are introduced. They must also be aware that labeling and SDS provide information about chemicals hazards.

6. Evaluate and reassess your program

Hazard communication programs must remain current. The best way to do this is to periodically reassess the program to make sure it is meeting its objectives and includes all hazardous chemicals in the workplace.

References: OSHA Hazard Communication Program Fact Sheet:

https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3696.pdf

Resources and examples for program development:

To protect workers from noise induced hearing loss OSHA has set an action level of 85 decibels (dBA) as a time-weighted average (TWA). OSHA requires employers to institute a hearing conservation program when workers are exposed to noise levels at or above the action level of 85 dBA or, equivalently, a dose of 50 percent. TWA exposures exceeding the OSHA permissible exposure limit of 90 dBA require feasible engineering or administrative controls to be implemented. An industrial hygienist can perform noise monitoring to determine noise levels in a facility. If there are job processes or areas of an operation where employees must raise their voices for the person next to them to hear, these areas may be above the action level of 85 dBA and warrant further investigation. In the cultivation of marijuana, loud noises could be generated by hand tools, wood chippers, if any landscaping equipment is being used by employees, or compressors to name a few.

An effective hearing conservation program can prevent hearing loss, improve employee morale, promote a general feeling of well-being, increase the quality of production and reduce the incidence of stress-related disease.

A hearing conservation program includes the following elements:

1. Monitoring program

A hearing conservation program requires employers to monitor noise exposure levels in a way that accurately identifies employees exposed to noise at or above 85 decibels (dB) averaged over eight working hours, or an eight-hour, time-weighted average (TWA). Employers must repeat monitoring whenever changes in production, process, or controls increase noise exposure. These changes may mean more employees need to be included in the program or their hearing protectors may no longer provide adequate protection.

2. Hearing protection devices

Employers must provide hearing protection devices to all employees at or above the action level. Employers must provide hearing protectors to all workers exposed to eight-hour TWA noise levels of 85 dBA or above. This requirement ensures employees have access to protectors before they experience any hearing loss.

Employees must wear hearing protectors:

Employers must provide employees with a selection of at least one variety of hearing plug and one variety of hearing muff. Employees should decide, with the help of a person trained to fit hearing protectors, which size and type protector is most suitable for the working environment. The protector selected should be comfortable to wear and offer sufficient protection to prevent hearing loss.

3. Employee training and education

All employees at or above the action level must be given training on the effects of noise on hearing and how and why to use various types of hearing protection devices. Employers must train employees exposed to TWAs of 85 dB and above at least annually in the effects of noise, the purpose, advantages, and disadvantages of various types of hearing protectors, the selection, fit, and care of protectors, and the purpose and procedures of audiometric testing. The training program may be structured in any format, with different portions conducted by different individuals and at different times, as long as the required topics are covered.

4. Audiometric evaluations

Employees that are a part of a hearing conservation program should be tested both at their hire and annually to determine if they have experienced any hearing loss. Audiometric tests must be performed by a licensed professional. Within six months of an employee’s first exposure at or above the action level, the employer shall establish a valid baseline audiogram against which subsequent audiograms can be compared. Audiograms should continue at least annually after obtaining the baseline audiogram for each employee exposed at or above an eight-hour, time-weighted average of 85 decibels.

5. Recordkeeping

Employers must retain data on exposure measurements and audiometric test results. Employers must keep noise exposure measurement records for two years and maintain records of audiometric test results for the duration of the affected employee's employment. Audiometric test records must include the employee's name and job classification, date, examiner's name, date of the last acoustic or exhaustive calibration, measurements of the background sound pressure levels in audiometric test rooms, and the employee's most recent noise exposure measurement.

Reference: OSHA Hearing Conservation Booklet:

https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3074/osha3074.html

Resources for additional program development: