Figure 1. A rescue crew

using a commercially

available cofferdam to

rescue a victim trapped

in grain (photo courtesy

of Liberty Rescue System)

Bodie Drake -Program Technician

Subodh Kulkarni, Ph.D. -Arkansas Program Associate

Karl Vandevender, Ph.D. -Professor, Extension Engineer

Grain bin entrapments are reminders that grain storage, especially flowing grain, may become very dangerous. Tragedies in have included suffocation when handling poultry feed, livestock feed, cottonseed, corn, rice and soybeans. According to statistics from Texas A&M University Extension, over 200 farmers have died as a result of grain bin suffocation accidents over the past 30 years.

According to an article in Resource by Matt Roberts and Bill Fields, in 2008 and 2009 the ratio of fatalities to non-fatal incidents has decreased when compared to earlier years. In 2009, 42 percent of entrapments resulted in death as compared to 45 percent in 2008 and 74 percent between 1964 and 2005. This increased rate of survival may be caused by increased emphasis on safer procedures, first responder training and commercially available grain rescue tubes (Figure 1), which were not available until 2007 or 2008. However, grain bins are still deadly. Consider some factors that contribute to this hazard.

In one instance, a 22-year-old man died in a corn storage bin in Missouri after he made a cell phone call for assistance. Assistance arrived within minutes, but they were too late. Donʼt make the mistake of your life. Be aware of the dangers of flowing grain or feed.

Due to health risks, entering bins should be avoided if possible. If entering a bin is being considered, all options – other than entering the bin – should be tried first. If it is essential for a person to enter the bin, wear a proper full body safety harness and tether manned by others outside.

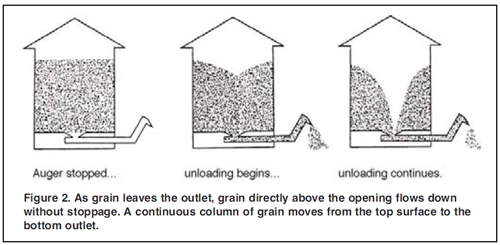

Why is flowing grain so dangerous? When the valve centered under the bottom of the bin is opened or the bottom unloading auger is turned on, grain or feed flows to the outlet. Figure 2 illustrates how the grain directly above the outlet replaces the discharged grain. This downward flow pattern immediately transmits to the top grain surface, starting a column of flowing grain. Very little grain volume moves within the bin. The grain across the bottom and away from the center of the bin does not move.

How rapidly the center column of grain is unloaded from the bin depends on the size of the opening and/or the conveyor capacity. The weight of a person standing on the grain forces the grain supporting him or her to flow to the outlet rapidly. This person’s weight is extra force that adds velocity to the grain underfoot and speeds the sinking victim.

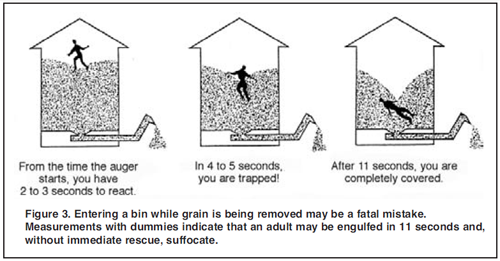

The rate at which grain is removed with the unloading auger or by gravity discharge from a valve makes engulfment more likely than many grain workers may realize. Bin unloading augers typically move grain from farm storage in Arkansas at 2,000 to 10,000 bushels per hour. At the slower 2,000 bushels per hour rate, this is approximately 41 cubic feet of grain moved per minute. The volume that a 6-foot-tall person takes up is roughly 7.5 cubic feet. At 41 cubic feet of grain movement per minute, the entire body of a 6-foot-tall person can be covered with grain in 11 seconds. If this happened to you in rapidly moving grain, you would be unable to free yourself before 5 seconds elapsed (Figure 3).

Grain may seem like flowing water, in that it exerts pressure over the entire surface of any submerged object. However, the amount of force required to pull someone up through grain is far greater than to rescue someone from under water. In fact, water has a buoyant force that “floats” ships and assists lifeguards in rescuing victims much larger than the lifeguard. Grain is much different. The predominant force is due to individual grains rubbing together to create a large friction force. This friction force along with the weight of the individual makes it very difficult to remove a victim buried in grain. Those who have rescued children who were partially covered with grain were surprised at the strength required. Typically, grain resistance pulls a person’s shoes off when he or she is drawn out. Research shows that 900 pounds of pull is required to raise an adult mannequin covered with wheat or corn. In essence, all but very well-prepared and well-equipped grain bin entrapment rescues are doomed to fail.

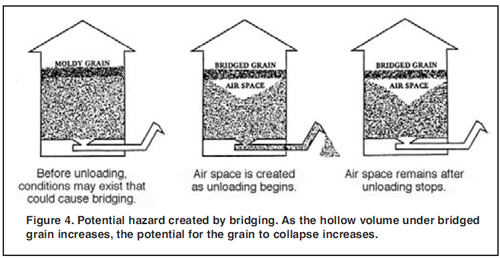

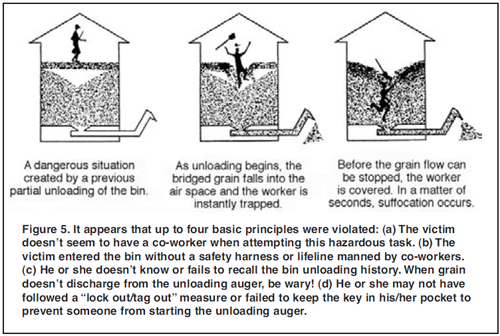

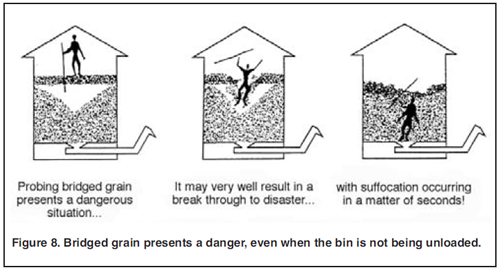

A similar tragedy may occur if someone enters a bin after grain “bridges” rather than flowing as individual kernels (Figure 4). Grain spoilage may cause grain to crust or bridge, thus resisting downward force that readily moves the loose grain to the bin outlet. Any hollow volume becomes a trap to a person who doesn’t avoid these hollow areas. Crusted grain rarely becomes hard enough to support a person (Figure 5). If a grain handler stops the grain from flowing out of the bin before he or she enters, that person may be covered anyway when the surface collapses under the person’s weight. As grain cascades down, the victim is covered with an “avalanche” of grain that traps and suffocates him or her.

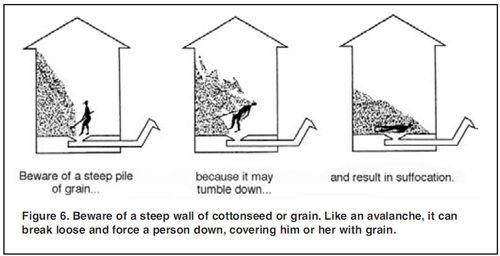

In a similar fashion, victims have died when rice or soybeans collapsed from a vertical wall. If a stack of grain does not flow to the bin outlet, a person may be prone to get a scoop or pole to poke the grain loose. Even though a wall of grain may appear perfectly safe, one scoop of grain removed may start an avalanche (Figure 6). If you are knocked off balance by the mass of grain, you are likely to be covered and suffocate. In certain cases, bumping the grain using a pole through one of the bin access covers may release the grain. Otherwise, do not enter the bin until a rescue crew is assembled should you get into trouble. Don’t enter without a body harness and a lifeline manned by at least two others. Lock out and tag out the power to the unloading auger before entry. Then start breaking up the hardened grain close to the top of the pile. This reduces the amount of loose, moving grain and thus its momentum, which could knock you over. (Also, there is less grain to cover you!)

Dislodging crusted grain can be very risky and should not be attempted without the correct tools and a well-planned response. This includes having at least two others assisting you as a team. The team should be well trained in grain rescue should someone become trapped. Don’t start this dangerous task of dislodging grain until your team and appropriate tools are at hand. Even during a busy period of work, you must be cautious enough to protect yourself and not compromise safety for the sake of getting the job done faster.

Entering a bin while the auger is operating is dangerous. There is no reason to enter a bin with an auger engaged. A slip near an auger with grid covers removed, whether it is caused by flowing grain or a misjudgment, may result in a traumatic entanglement. Always advise others of your intentions before you enter a bin. Equip yourself by getting others to hold a tether attached to your body harness while you work in the bin safely.

Personally ensure that no one will engage power to activate augers or load into the bin while you are inside. OSHA 29 CFR 1928.57 regulations require employees* to follow “lock out/tag out” procedure. Lock the lever “off” on the electric control box with your padlock and place the key to the padlock in your pocket. Padlocks are readily available for this purpose at local electrical supply businesses.

Engulfment is less common in gravity-unloaded systems, but it can occur when grain or feed is discharged into or “dumped” onto an unsuspecting person in a bin. Not working alone, coordinating with a rescue team and not entering a bin without a safety harness are necessary precautions for avoiding these tragedies.

*Farms are not covered by OSHA jurisdiction unless they employ more than 10 employees. The Federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has confined space entry regulations under 29CFR, article 1910 146, that may apply to workers.

Airborne grain dust, microbial spores and inadequate oxygen to sustain breathing can cause the death or sickness of a person entering a grain bin (confined space). Persistent exposure to these airborne particles may cause “farmer’s lung,” which may lead to an irreversible lung condition and may eventually cause death. Flowing grain hazards plus mold and dust health hazards may exist when working with grain that has gone out of condition or has bridged into a precarious stack. Those who enter should wear NIOSH-approved dust-filtering respirators to protect their lungs. Other more effective filtering equipment may prove to be a better alternative for extended exposures.

Workers entering a grain or feed bin should have a body harness tethered to a lifeline that is manned by two others outside the bin. One worker should be able to see the worker inside the bin through an access. This support crew can retrieve the one who entered the bin. One rescuer can get aid, if necessary, after the victim is retrieved, while the other is treating the victim. Don’t depend on being able to be heard from the inside to the outside of the bin. The use of prearranged arm and hand signals is one suggestion for these conditions. It is difficult to hear when grain-handling or drying equipment is operating.

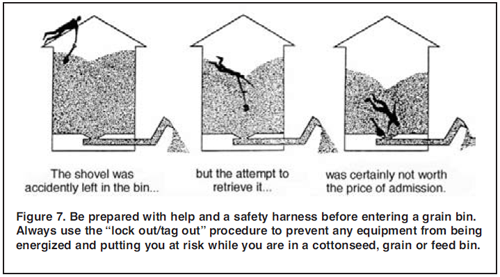

Never enter a bin of flowing grain. If you drop a grain probe or shovel, first stop the flow of grain, take the precautions given in Rule 1, then retrieve the lost item. Remember, no piece of equipment is worth a human life (Figure 7).

You should know or be wary about a grain bin’s history before entering. Get help if the grain surface appears moldy or caked. Get at least two helpers and have a tether and a safety harness (Rule 1). Strike the grain surface hard with a pole or long-handled tool before entry. Probe through the top layer and determine if there is a crusted surface (Figure 8); never get out of communication with your co-workers.

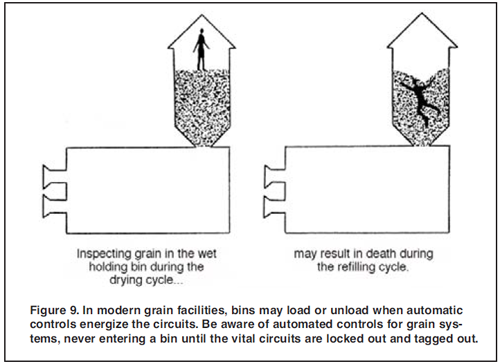

Don’t fail to lock out/tag out related power equipment before entering any bin (Figure 9). It may also be wise to post a sign on the control box if it is possible that others may arrive after you padlock the control levers. If a bin is unloaded by gravity flow, padlock the control gate to keep it closed.

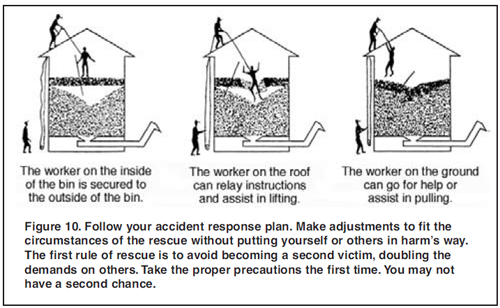

An accident response plan was mentioned toward the beginning of this publication (Figure 10). Any adjustments to rescue another should not endanger a second victim. A rescue should not increase the number of nor the severity of injury to victims. Having appropriate breathing apparatus is essential if the victim has been unable to get sufficient oxygen or has been breathing air containing grain toxins. Use adequate dust protection, and take a rope to remove the victim from the bin without using your tether. Again, an adequate crew is essential to retrieve a victim without placing yourself in the same danger! Before concluding that you should enter a bin, make sure adequate help is available to pull you out with your tether and safety harness.

Preventative safety measures should include proper ladders, scaffolds, etc. Modern bins have an interior ladder, and these can be installed in older bins. Have a body harness, tether, breathing apparatus and a minimum of two others in your crew if you have reason to enter a bin. Remember, always try to alleviate a problem without entering the grain bin. Do not enter without following all accident prevention measures, having a trained crew and using the recommended equipment

Remember, if you become trapped, you will need to get help. Getting help and successfully being rescued is much easier if you have an accident response plan. Contact your help waiting outside the bin. Pulling a person from grain can be very difficult due to the friction forces transferred from the grain to the person. Do not attempt to winch a person from grain if the person is buried deeper than knee deep. This may cause joint dislocation, paralysis and other severe injuries. The grain must be removed from around the person to get him or her out. You can do this by cutting holes in the side of the grain bin or by creating a cofferdam around the person and bailing out grain with a shop vac or a bucket. Grain cofferdams can be constructed by driving sheets of plywood around the person. They can also be constructed out of plastic barrels. Currently, there are several commercially available grain rescue tubes with interlocking pieces that are connected and driven into the grain to create a cofferdam. Commercial rescue tubes typically have steps on the inside to assist the victim in climbing out of the grain.

Discuss the safety hazards of grain dryers and bins and feed-handling and storage facilities with your family and employees. Make specific accident response plans with employees and anyone, such as a trucker, who frequently works around the facility. Each has the responsibility to be aware of potentially unsafe conditions and to take steps to remedy them. By working together as a team, more of the dangers will be identified and more practical remedies will be taken. If you use a team approach, the potential of entanglement or suffocation is almost eliminated.

Hand Signals for Use in Agriculture, ASAE S351. 2005.

American Society of Agricultural Engineers Standards,

St. Joseph, MI.

Kingman, D. M., W. E. Field and D. E. Maier. 2001.

“Summary of Fatal Entrapments in On-Farm Grain

Storage Bins, 1966-1998,” Journal of Agricultural

Health and Safety, Vol. 7(3):169-184, St. Joseph, MI.

McKenzie, B. L. A., “Suffocation Hazards in Flowing Grain,”

Agricultural Engineering Department, Purdue

University, West Lafayette, IN.

Roberts, M., and B. Field. 2010, July/August. A Disturbing

Trend: U.S. Grain Entrapments on the Increase.

Resource, American Society of Agricultural and

Biological Engineers, 10-11.

Acknowledgments: Dennis Gardisser, retired Extension engineer and professor, and Gary Huitink, retired Extension engineer and associate professor, are acknowledged for their development of this publication. The graphics were adapted from a publication by Bringle Jennings, former extension specialist, University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture, Little Rock; Dr. Otto Loewer, Jr., professor, Biological and Agricultural Engineering, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville; and Dr. David H. Loewer, Wynne, Arkansas.

BODIE DRAKE is program technician, DR. SUBODH KULKARNI is program associate and DR. KARL VANDEVENDER is professor Extension engineer, Biological and Agricultural Engineering, University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture, Little Rock.

FSA1010-PD-9-10RV

Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Director, Cooperative Extension Service, University of Arkansas. The Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service offers its programs to all eligible persons regardless of race, color, national origin, religion, gender, age, disability, marital or veteran status, or any other legally protected status, and is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer.

Publication #: FSA1010-PD-9-10RV

Disclaimer and Reproduction Information: Information in NASD does not represent NIOSH policy. Information included in NASD appears by permission of the author and/or copyright holder. More